A Review of UNCTAD’s ‘Aid at the Crossroads’

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) have recently released a report entitled Aid at the Crossroads: Trends in Official Development Assistance which aims to provide an overview of the global Official Development Assistance (ODA) picture. It provides understandings on current rates of ODA, who is providing what, and how ODA is being used by recipient countries. It also provides helpful pointers as to what may be coming next. It also provides insight into where the coming Financing for Development 4 Conference in Seville may focus its efforts. In this short piece, the focus will be on a. identifying some of the more pertinent pieces of data revealed by the report, and b. contextualising the data from the perspective of the debt crisis and the ‘credit rating impasse’.

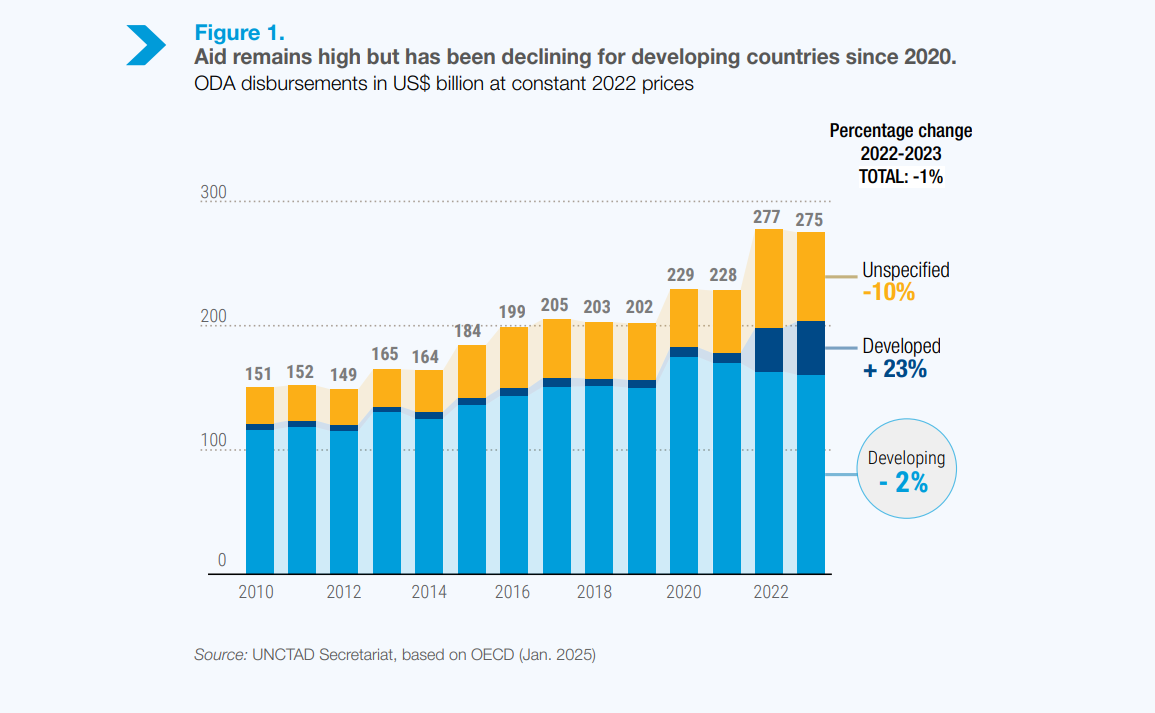

ODA remains high but has declined for developing regions for the third year running

Whilst ODA reached a record level in 2022, it actually decreased in real terms in 2023. ODA remained high during 2023, increasing by 4%, but accelerating global inflation meant that this 4% increase resulted in a decline of 1% in real terms. The result, as the report notes, is that ‘the actual purchasing power of aid – and therefore its impact – diminished due to inflation’.

In relation to developing countries, the situation is stark. The report reveals that ODA to developing countries decreased for the third year in a row; in 2023 it stood at $160bn, $15bn less than at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Conversely, ODA towards developed countries, to be spent on issues such as refugees and asylum seekers (as well as Ukraine) increased by 23%.

When examined on a regional perspective, this loss for the developing world is felt most intensely in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. The report illustrates that ODA decreased the fastest for Latin America and the Caribbean (down 14.5%) and that Africa saw the biggest decrease in absolute terms, down by 6.8%, or $5.3 billion. As the report notes, ‘the protracted decline in aid to Africa is particularly severe, as the region accounts for the majority of men and women living in extreme poverty, suffering from compounding forms of deprivations’.

Taking a more granular view, Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS) have also been on the negative side of ODA rates, although in 2023 rates for both groups actually rebounded, with LDCs receiving 3.5% more and SIDS receiving 2.6% more. However, landlocked developing countries saw their share decrease by more than 5.5%, returning that group to pre-COVID levels.

Where Does ODA Come From?

While ODA from multilateral donors has been increasing, the majority still comes from bilateral sources. Notable multilateral donors include the International Development Association (IDA) which accounting for almost half of all multilateral aid between 2022 and 2023 ($24 billion). However, the vast majority does indeed come from ‘Development Assistance Committee’ (DAC) and non-DAC donors. Notable DAC donors include the USA, the UK, the EU (and various European Countries), and Australia while notable non-DAC countries include China, Russia, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia. DAC countries contributed the most ODA by far, but its rate of contribution continues to decline. In 2023, contributions from DAC countries accounted for 61% of ODA, down from more than 70% just a decade ago. In contrast, multilateral aid has been stable, at around 25%. As a result, the role of the multilateral aid provider has become more important for the developing world, with more than 30% of developing world aid now coming from multilateral donors.

There has also been a welcome shift in ODA grants compared to ODA loans. This is in a worsening context however, as the report notes that ‘the share of ODA grants in total ODA has been continuously falling over the past two decades’. Between 2010 and 2020 grants made up 70% of total ODA, but since the pandemic that figure has fluctuated (at its lowest to below 65%, but in 2023 rebounding to 67%). This rebounding as been welcome. In 2023, ODA loans dropped to $52 billion, ODA grants increased to $108 billion, and equity investments plummeted to just $300 million. However, when viewed from the regional perspective, ODA rates for both loans and grants reveal staggering pictures: for Africa, both loans and grants decline by 6% each.

What is the ODA being spent on?

The report shows that ODA is mostly being directed towards social infrastructure and services, representing 39% of the total. Other avenues include Economic Infrastructure and services, Humanitarian Aid, and Production Sectors. Granularly, Humanitarian Aid has been the fastest growing ODA item for the past 15 years and has witnessed a double-digit expansion. Important, despite increasing concern about debt sustainability, ODA for ‘debt action’ has continued to decline; it reached an historic low in 2023. Also, after further disaggregation, it is Health that is suffering the largest decline, down 27%.

What next?

With FFD4 in Sevilla only three months away, the report opines on what the Conference should focus on after ingesting the report’s data. The report also provides key commentary on the global environment. First, it notes that the aid target of the SDGs remains nearly 50% unmet. It notes that DAC donated ODA in 2022 and 2023 represented only half of what was targeted – 0.37% of Gross National Income compared to 0.7%. Only Norway, Sweden, Luxembourg, Germany, and Denmark achieved their SDG target. Second, public announcements regarding ODA and providing wider support have become particularly negative in recent years. Political and media focus has been actively turning towards fiscal consolidation and defence spending, which has resulted in clear confirmation that aid provisions will be reduced. Because of all of these issues, the report concludes with four priorities moving forward:

Get updates from Daniel - Sign up to the Email list here: https://mailchi.mp/7a43146873f0/email-list-for-dr-daniel-cash