Blog

Development and Debt: Power, Vulnerability, and the Architecture of Reform

Debt distress in developing economies is no longer a passing liquidity issue. It is a structural governance problem that privileges creditor leverage over development outcomes, draining fiscal space and constraining the Sustainable Development Goals. This piece examines how the “credit rating impasse” — the practice of classifying IMF-backed restructurings as defaults when private creditors are involved — deters governments from using formal debt treatment mechanisms. It unpacks the legal jurisdictions, holdout risks, and trade vulnerabilities that reinforce this deterrent, and makes the case for a safe-harbour procedure to protect compliant restructurings from punitive ratings. Without reform that links debt architecture to the credit rating process, relief will continue to be penalised precisely when it is most needed.

The debt stress facing developing economies is not a passing liquidity squeeze; it reflects a governance imbalance that still privileges creditor leverage over development outcomes. Public resources are being diverted on a vast scale from social investment toward debt service, with direct consequences for the Sustainable Development Goals.

Between 2020 and 2025, lower-income countries directed 39% of external debt service to private creditors, 34% to multilaterals, 13% to Chinese lenders, and 14% to other governments. In many of the highest-burden cases, private creditors capture the largest share. The familiar storyline that singles out China misses where most of the money actually flows.

This skew exposes a deeper flaw: the credit rating impasse. Countries with sizeable private external debt now face a structural deterrent to using formal treatments precisely when they need them most. Once private creditors must be included for comparability of treatment, rating agencies classify the process as a default. Participation in an exchange or a standstill typically triggers default designations such as SD or D at S&P, RD at Fitch, or limited-default treatment at Moody's, even when the operation is part of an IMF or G20-backed path to sustainability. Earlier Paris Club–only workouts often escaped this because marketable private instruments were not in play. The result today is hesitation: governments delay requests for the Common Framework or resort to ad hoc re-profilings to avoid the default tag that raises funding costs and shuts market access at the very moment relief is meant to arrive.

Jurisdiction magnifies this deterrent. Most bonds eligible under the G20 Common Framework are governed by English or New York law, venues whose enforcement powers tilt negotiations toward creditors and increase the likelihood of holdout litigation. The 2012 Argentina litigation remains the defining precedent. Judge Griesa’s pari passu injunctions, affirmed by the Second Circuit and left untouched by the US Supreme Court, blocked Argentina from paying exchange bondholders unless holdouts were paid in full. S&P declared a selective default that July when Argentina missed payments because of the court order. The episode not only froze Argentina out of markets until 2016 but reshaped creditor expectations: governments now know that holdouts can invoke similar tactics, making rating downgrades more probable and restructuring timelines longer.

The holdout problem feeds directly into rating agency assessments. Without a sovereign bankruptcy regime, a minority of creditors can delay or derail settlements, forcing official and cooperative creditors to absorb deeper losses and leaving debtors with less fiscal space. The Common Framework’s reliance on equitable burden-sharing becomes a weakness when that equity is hostage to holdouts. Rating agencies price in this litigation risk, which increases the likelihood of a default classification when private creditors are involved. Countries are therefore discouraged from using the very mechanism intended to help them.

Trade vulnerabilities intensify the cycle. Export revenues underpin debt sustainability, yet protectionist shifts and geopolitical fragmentation threaten those earnings. The IMF estimates that sustained protectionism could lower global output by up to 7% over the long run. This erodes repayment capacity while making downgrades more damaging, particularly for export-dependent economies that rely on market access to finance trade and refinance maturing debt. Debt-to-export ratios among IDA borrowers climbed from 117% in 2013 to 190% in 2023, peaking at 240% during the pandemic. Industrial policy choices in advanced economies - such as re-shoring and friend-shoring - can therefore squeeze fiscal space in developing ones through trade channels.

Domestic debt pressures extend the deterrent’s reach. Local-currency issuance reduces foreign-exchange risk, but rising domestic service costs now compete directly with core development spending. When a downgrade threatens not just external market access but also the rollover of domestic debt, governments become even more cautious about triggering it. The impasse thus envelops the whole borrowing profile, not just external obligations.

Institutional reform offers partial insulation. Saint Lucia cut its debt-to-GDP ratio from over 90% in 2020 to 74.5% in 2024 by overhauling its borrowing framework, coordinating its debt office, and adopting the Commonwealth Meridian system for real-time monitoring. The Bahamas is following a similar path. These are not silver bullets but demonstrations that governance, technology, and predictable market engagement can push distress thresholds further away.

The most decisive fix would be a safe-harbour procedure embedded in the debt architecture. Official treatments that meet defined standards - IMF programme support, broad creditor participation, transparent debt sustainability analysis - could be classified as ‘distressed exchanges’ rather than defaults. This would mirror the way agencies distinguish between corporate restructurings intended to restore viability and those signalling abandonment. Piloting such guidance for Common Framework cases could reduce the deterrent effect without compromising analytical integrity.

The 4th Financing for Development Conference in Sevilla produced an agenda of automatic standstills, faster and broader treatment under the Common Framework, climate-resilient debt clauses, and re-channelled SDRs. These measures are necessary but not sufficient. Unless the debt architecture is aligned with the credit rating process, the impasse will continue to undermine the tools designed to restore sustainability.

Sovereign debt can be treated as a technical cycle to be managed or as a governance challenge to be redesigned. If creditor rights remain unbalanced by obligations to participate in equitable restructurings, if debtor institutions cannot manage risk in real time, and if procedural reforms are not embedded to avoid needless default labels, the system will keep penalising relief when it is most needed. That is the essence of the credit rating impasse: a safety net turned into a trap.

The Two Empires of Credit Ratings: Strategy, Power, and the Moody’s vs S&P Global Narrative

Recent articles from Seeking Alpha and AInvest suggest Moody’s is ‘lagging’ behind S&P Global’s superior performance and market responsiveness. This framing reduces a complex story to a simple scoreboard, missing the deeper architecture at work. The comparison between these agencies reveals two distinct models of credit rating power operating within the same global financial system - not a winner and a loser, but complementary approaches to wielding influence over debt markets.

Understanding their strategic divergence matters because these are not ordinary corporations. They issue the signals that move sovereign and corporate borrowing costs, shape infrastructure financing and economic development, and determine access to capital markets for millions of borrowers worldwide. How they organise their authority tells us something important about the logic of contemporary financial governance.

S&P’s Strategy: Breadth as Influence

S&P Global has built what amounts to market-wide infrastructure. Beyond credit ratings, it operates the indices that define how trillions in assets are allocated, provides commodity price benchmarks that set global energy costs, and maintains the data systems that institutional investors use to make allocation decisions. The $44 billion IHS Markit acquisition in 2022 was the clearest expression of this philosophy - transforming S&P from a financial services firm into what CEO Douglas Peterson called ‘essential intelligence’ for global markets.

The strategy is about positioning S&P at multiple chokepoints in the financial system. When Peterson describes the company’s mission as helping clients ‘push past expected observations and seek out new levels of understanding’, he is articulating a vision of comprehensive market intelligence rather than specialised advisory services.³ The recent decision to spin off the $1.6 billion Mobility division signals a continued focus on core financial infrastructure rather than diversification for its own sake.

This approach creates what Peterson terms ‘powerful software, advanced tools, and the ability to harness insights within a highly efficient workflow’. It is less about being the definitive voice on credit risk and more about becoming the operating system that financial markets run on. S&P’s 80% recurring revenue across non-ratings segments reflects this infrastructure-building logic - once institutions integrate these systems into their workflows, switching costs become prohibitive.

Moody’s Strategy: Depth as Authority

Moody’s has pursued the opposite approach. Where S&P built breadth, Moody’s doubled down on being the definitive authority on credit risk assessment. CEO Rob Fauber frames this as serving clients who need to ‘develop a holistic view of their world and unlock opportunities’ in what he calls a ‘world shaped by increasingly interconnected risks’.

The strategy shows up in Moody’s acquisition pattern - targeted purchases like Cape Analytics for geospatial risk intelligence, climate risk modelling capabilities, and enterprise risk solutions. These are not attempts to build comprehensive market infrastructure. They are investments in becoming better at the core function: assessing the probability that borrowers will default.

Fauber’s recent remarks to the Council on Foreign Relations position Moody’s as ‘the Agency of Choice’ for complex risk assessment. This language reflects a belief that specialised expertise commands premium valuations. Rather than competing on workflow integration, Moody’s competes on analytical sophistication and methodological rigour.

The depth strategy creates different competitive dynamics. Moody’s recent acquisitions and partnerships, including Cape Analytics and its strategic AI collaboration with Microsoft, aim to enhance its core credit assessment capabilities rather than expand into adjacent markets. The result is higher operating margins (48% vs S&P’s 35%) but greater exposure to credit cycle volatility.

Technology Investment: Different Views of Competitive Advantage

The companies’ approaches to AI and technology reveal their strategic philosophies in microcosm. Moody’s has pursued deep partnership with Microsoft, deploying AI tools across its analyst base to enhance the quality of credit analysis rather than automate it away. S&P Global has taken a broader approach, training its entire 35,000-person workforce in generative AI while acquiring companies like ProntoNLP and TeraHelix to embed AI capabilities across its platform.

Neither approach is inherently superior, but they reflect different theories about where technology creates sustainable competitive advantages. Moody’s bets that AI enhances human expertise in complex risk assessment. S&P Global bets that AI enables new forms of systematic market analysis at scale.

Reputation and Power: Two Empires in One System

The market has sorted these approaches into distinct roles. S&P Global is perceived as the diversified growth engine - the company that builds the financial system’s infrastructure. Analysts consistently describe it as ‘more innovative’ and ‘strategically aggressive’ in pursuing new markets and capabilities.

Moody’s is seen as the resilient precision operator - the company that provides authoritative judgment on complex credit decisions. Investment analysis consistently notes Moody’s higher margins and return on capital, but also its greater cyclical exposure.

This creates a duopoly of power where each agency reinforces different logics of financial governance. S&P Global’s systematic, data-driven approach appeals to institutions that need consistent, comparable risk assessment across large portfolios. Moody’s forward-looking, judgment-heavy approach appeals to institutions making complex, one-off credit decisions where analytical depth matters more than systematic comparability. This is not to say that these roles are absolute, of course, but they are broadly accurate.

The divergence shows up in their client relationships and use cases. S&P Global’s infrastructure model makes it indispensable for passive investment management, index construction, and systematic risk management. Moody’s authority model makes it essential for active credit selection, complex structured finance, and situations where regulatory approval requires the imprimatur of analytical expertise.

This is not about one agency ‘lagging’ another. It is about strategic orientation creating different forms of market power that serve different institutional needs.

Conclusion: Why This Matters

Credit ratings are not technical assessments issued by neutral arbiters. They are public signals issued by private institutions that determine access to capital for governments, corporations, and projects worldwide. The strategic choices these agencies make - toward breadth or depth, infrastructure or expertise, systematic process or analytical judgment - shape how risk gets defined and measured in global markets.

Recent regulatory scrutiny, including SEC penalties for recordkeeping failures, highlights the importance of understanding how these institutions organise their authority. Reform efforts that treat them as interchangeable utilities miss the point. They have evolved different approaches to wielding influence precisely because markets demand different forms of risk intelligence.

This is not a story of one agency falling behind. It is a rare case of two firms thriving on opposite sides of the same financial ecosystem - each shaping the rules of global credit in their own way. To understand rating power today, we need to see the system not as a race, but as a balance of depth and breadth.

Rather than asking which agency is ‘winning’, we should ask what their strategic divergence tells us about the evolving logic of financial governance. The answer reveals two empires operating within one system, each pursuing different forms of influence over the flows of global capital.

📺 Watch on YouTube: Rated – with Daniel Cash

Explainer videos on how credit rating agencies shape the world

→ https://www.youtube.com/@RatedwithDanielCash

📸 Follow on Instagram: @RatedWithDanielCash

Visual explainers, quotes, and reform insights

→ https://www.instagram.com/ratedwithdanielcash/

🎥 Follow on TikTok: @RatedWithDanielCash

Short videos breaking down how credit ratings really work

→ https://www.tiktok.com/@ratedwithdanielcash

📰 Read on Substack: Rated Dispatches

Essays and reflections on how credit rating power shapes global finance

→ https://substack.com/@ratedwithdanielcash

💼 Connect on LinkedIn: Dr. Daniel Cash

→ https://www.linkedin.com/in/daniel-cash-61684623/

🌐 Visit: www.drdanielcash.com

Writing, research, and reform work all in one place

What RMB Growth Means for Ratings: Credit Risk in a Multipolar Africa

What RMB Means for Ratings: Credit Risk in a Multipolar Africa

As African countries explore RMB-denominated bonds, currency swap agreements, and alternatives to SWIFT, a deeper shift is underway — one that credit rating agencies are not yet equipped to handle. This analysis examines how China’s expanding financial infrastructure across Africa is exposing gaps in traditional rating methodologies, and what it will take for CRAs to remain credible in a world where financial sovereignty increasingly moves through currency and architecture, not just policy. This is not about bias — it’s about readiness.

China’s accelerating RMB internationalisation across Africa is creating new financing pathways that challenge traditional credit risk assessment frameworks. Egypt’s landmark Panda bond issuance and Standard Bank’s direct CIPS participation mark watershed moments in African capital markets. Yet credit rating agencies struggle to adapt methodologies designed for dollar-denominated, Western-intermediated flows to account for multipolar currency dynamics. The core question emerges: How should credit rating agencies evolve to reflect a world where financial infrastructure, not just currency, is diversifying?

RMB Instruments Gain Ground, but Constraints Remain

Egypt’s breakthrough Panda bond has established a credible template for African sovereign RMB financing. The RMB 3.5 billion ($478.7 million) sustainable bond issued in October 2023 achieved a competitive 3.51% coupon rate, backed by African Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank guarantees. This transaction won ‘Africa’s Best Bond Deal for 2024’ and demonstrated RMB market viability when China’s benchmark rates fell to historic lows. Kenya has announced plans for a $500 million Panda bond debut in fiscal year 2024, seeking alternatives to expensive Eurobond markets amid debt challenges. Meanwhile, Afreximbank achieved AAA rating from China Chengxin International Credit Rating (CCXI) in early 2025, becoming the first African multilateral to receive this designation in China.

Cross-border payment infrastructure is evolving rapidly. Standard Bank of South Africa became the first African bank to join CIPS as a direct participant in January 2025. These moves are not just technical - they reflect strategic efforts by African institutions to broaden financial sovereignty through infrastructure, not just ideology. African CIPS participation has grown from 52 indirect participants in July 2024 to 59 by April 2025, with processing times reduced from 3-5 days via SWIFT to seconds through CIPS.

However, structural constraints persist. Africa’s trade deficit with China limits natural RMB flows, while capital controls and restricted convertibility constrain broader adoption. Most China-Africa transactions continue in USD despite official encouragement for RMB usage.

CRA Frameworks Are Still Playing Catch-Up

Major Western credit rating agencies have not published systematic methodology updates specifically addressing RMB exposure for African sovereigns, despite increased Panda bond activity and CIPS integration. Current evaluation approaches treat China-related risks within existing external debt frameworks rather than developing RMB-specific assessment tools.

S&P Global noted the 82% increase in Panda bond issuance in 2023, calling 2024 ‘the best for panda bond issuance since the market opened in 2005’. However, this remains market commentary rather than formal methodology guidance. Agency assessments appear to view payment system diversification through a risk-benefit lens - recognising reduced SWIFT dependency benefits while noting increased dependence on Chinese financial infrastructure. Currency swap agreements receive minimal explicit coverage in published methodologies. CIPS processed RMB 123.06 trillion ($17.09 trillion) in 2023 across 1,427 financial institutions, yet agencies lack formal frameworks for evaluating the payment system integration’s credit implications.

The methodological gap creates assessment challenges. Agencies consistently cite opacity in Chinese loan agreements as complicating risk evaluation, with restructuring approaches differing from traditional Paris Club frameworks through bilateral negotiations.

Research reveals systematic differences between Chinese and Western CRA models

Academic studies of Chinese credit rating agencies identify systematic methodological divergences from Western approaches that extend beyond simple grade inflation. Research analysing jointly-rated entities finds Chinese agencies rate issuers 6-7 notches higher than Western counterparts, reflecting fundamental differences in risk assessment frameworks. Asset size receives dramatically different treatment in Chinese methodologies. Studies show domestic agencies favour larger firms significantly more than Western counterparts, measuring physical assets and tangible infrastructure as stronger positive credit factors. Research finds Chinese agencies show statistically insignificant coefficients on leverage while Western agencies treat it as strongly negative.

Analyses of Chinese sovereign rating patterns suggest geographical considerations play a role in assessments. Academic research examining Belt and Road Initiative financing treatment finds that Chinese foreign investment adversely affects sovereign ratings when countries participate officially in BRI according to Western methodologies, while Chinese CRAs view BRI infrastructure investment as credit-positive for recipient nations. Market data reveals complexity in dual-rated instrument pricing. Bonds rated by Chinese CRAs command different yields than Western-rated equivalents, but credit spreads correlate more strongly with Western ratings, highlighting methodological credibility differentials in international markets.

Currency diversification benefits compete with liquidity constraints

Offshore RMB liquidity remains structurally limited despite internationalisation efforts. CNH deposits represent approximately ¥1.5 trillion, only 1% of onshore deposits versus 30% for offshore USD. RMB represents only 2.5% of international currency usage versus 66% for USD. Currency diversification trends show modest but measurable shifts. ECB research shows continued reserve diversification into non-traditional currencies, with RMB-denominated credit to emerging markets increasing $240 billion since early 2022 while USD credit fell $380 billion. However, RMB holds only 2.3% of allocated FX reserves versus its economic weight.

African sovereign debt markets face elevated pricing. Countries experience an estimated ‘African premium’ of 2.9 percentage points above fair borrowing rates, making RMB financing attractive when Chinese rates are low, but adoption remains constrained by market access limitations.

African sovereigns achieve rating improvements despite participation complexities

All three major African countries with significant China exposure received positive outlook revisions in 2024-2025. Egypt gained positive outlooks from all three major agencies following IMF program expansion. Nigeria received positive outlook from Fitch amid reform progress. South Africa earned positive outlook from S&P following Government of National Unity formation. Market access has improved but pricing remains elevated. After nearly two-year hiatus, African sovereigns returned to Eurobond markets in Q1 2024 with oversubscribed issuances from Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, and Kenya. However, average coupon rates of 8.5% significantly exceed refinanced debt costs, reflecting elevated risk perceptions. Chinese lending data shows $182.28 billion in loans across 1,306 transactions to 49 African countries, with 2023 marking first increase since 2016. However, 56% of 2023 lending ($2.59 billion) focused on financial institutions rather than direct sovereign exposure, indicating evolving Chinese risk management approaches.

Conclusion: When financial architecture changes, the logic of credit must evolve

The evidence reveals a fundamental disconnect between rapidly evolving financial infrastructure and static credit assessment methodologies. A Panda bond with a domestic AAA rating - issued in RMB, guaranteed by multilaterals, and yet interpreted through legacy CRA models - signals a system under stress.

Credit rating agencies must develop sophisticated frameworks for evaluating multipolar currency dynamics, moving beyond ad hoc assessments within existing external debt models. The systematic differences between Chinese and Western agency methodologies create market confusion and potential mispricing of dual-rated instruments that could become increasingly common.

For African policymakers and multilateral officials, the evidence suggests measured optimism about RMB diversification benefits while maintaining realistic expectations about scale and timeline. Currency diversification can reduce USD concentration risks and potentially lower borrowing costs in favourable Chinese interest rate environments, but requires careful balancing against liquidity constraints and methodological recognition challenges.

This is not about bias – it is about readiness. RMB internationalisation is real, but its credit logic remains under-theorised. As financial sovereignty increasingly operates through currency and payment infrastructure, rating agencies that fail to adapt risk obsolescence in a multipolar world where African governments are constructing more resilient and strategic credit narratives.

📺 Watch on Youtube: Rated – with Daniel Cash

Explainer videos on how credit rating agencies shape the world

→ youtube.com/@RatedWithDanielCash

📸 Follow: @RatedWithDanielCash on Instagram

Visual explainers, quotes, and reform insights

→ instagram.com/RatedWithDanielCash

💼 Connect: Dr. Daniel Cash on LinkedIn

→ linkedin.com/in/daniel-cash-61684623

🌐 Visit: www.drdanielcash.com

Writing, research, and reform work all in one place

When the Numbers Don’t Add Up: What Senegal’s Downgrade Reveals About Hidden Debt and Credit Ratings

Senegal’s dramatic two-notch downgrade to B3 in February 2025 by Moody’s has been followed by S&P downgrading to B- earlier this week, sending shockwaves through African bond markets, but a comprehensive new analysis from Moody’s suggests this kind of debt revision is rarely an isolated incident. The rating agency’s July 17, 2025 report on ‘Large, unaccounted for, debt increases‘ provides crucial context for understanding how fiscal transparency failures systematically undermine sovereign creditworthiness - not just in Africa, but globally.

What Moody’s Found: Stock-Flow Adjustments as Early Warning Signals

Moody’s latest research centres on stock-flow adjustments (SFAs) - discrepancies between annual changes in debt stocks and what budget deficits alone would predict. These adjustments capture debt increases that cannot be explained by identifiable components such as economic growth, fiscal deficits, or exchange rate fluctuations. When persistent and large, they often signal underlying transparency weaknesses or incomplete fiscal reporting.

The agency finds that large and persistent stock-flow adjustments often signal weak fiscal transparency and that, over time, they reflect incomplete reporting and weak expenditure controls. Critically, Moody’s notes that ‘frontier markets in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America have experienced the biggest stock flow adjustments over the past decade’. The technical drivers behind SFAs are diverse and often legitimate, including debt management operations, asset acquisitions, arrears clearance, and statistical revisions. However, Moody’s research indicates that ‘around half of non-FX driven changes in stock-flow accumulations in low-income countries originated from arrears, revision in debt statistics, bank and SOE recapitalisations, off-budget transactions and undisclosed debt that was later uncovered’. The other half remained unexplained - an indicator Moody’s treats as a serious red flag for fiscal credibility.

Senegal’s Fiscal Picture: A Case Study in Transparency Failure

Senegal’s situation exemplifies how transparency gaps can rapidly destabilise sovereign credit profiles. Following the March 2024 election, audit findings by the Inspectorate of Public Finances and subsequent Court of Auditors report revealed ‘substantially weaker fiscal metrics’ with ‘central government debt at close to 100% of GDP in 2023, around 25 percentage points higher than previously published’.

The scale of the revisions was unprecedented: debt-to-GDP ratios jumped from a reported 74.4% to 99.7% for end-2023, while the fiscal deficit was revised upward from 4.9% to 12.3% of GDP. Moody’s assessment was unambiguous: ‘The scale and nature of the discrepancies portray a much more limited fiscal space and higher funding needs than previously thought, while also indicating material past governance deficiencies’. The rating impact was swift and severe. Moody’s downgraded Senegal’s rating to B3 from B1 in February 2025, changing the outlook to negative, following an earlier downgrade from Ba3 in October 2024. This marked a three-notch deterioration in four months - one of the fastest downward rating trajectories for a sovereign outside of default events.

Current debt metrics reflect the severity of the fiscal challenge. The IMF estimates Senegal’s debt reached 105.7% of GDP by end-2024, with gross financing requirements of approximately 20% of GDP projected for 2025. The IMF suspended its $1.8 billion Extended Credit Facility in June 2024 following the misreporting discovery, while Senegal’s Eurobonds declined significantly, with 2033 bonds falling to around 80 cents on the dollar.

A Global Pattern, Not an African Exception

While African cases dominate recent headlines, Moody’s emphasises that stock-flow adjustments occur across all regions and income levels. The agency notes that ‘stock-flow adjustments have many underlying causes, and are common across advanced economies and emerging and frontier markets alike’. For context, Eurostat monitoring shows that several EU countries recorded SFAs in the 1-4% of GDP range in 2024, underlining that this phenomenon is present even in advanced economies.

However, the persistence and magnitude differ significantly by region. Recent African cases demonstrate particularly troubling patterns:

Mozambique’s 2016 revelation involved undisclosed debt amounting to 10% of GDP through state-owned enterprises, leading to sovereign default and an estimated economic impact approaching the country’s entire 2016 GDP. The so-called ‘tuna bonds’ scandal involved $2.2 billion in secret government guarantees arranged through Credit Suisse and VTB Capital.

Zambia’s complex debt structure contributed to its 2020 default, with opacity stemming from state-owned enterprise borrowing not fully consolidated in sovereign statistics. The total debt involved 44 different lending entities across multiple jurisdictions, complicating both transparency and eventual restructuring efforts.

Republic of Congo’s 2017 discovery revealed substantial oil-backed debt structured through offshore entities, with total obligations reaching levels significantly above initially reported figures.

Gabon’s post-2023 transition disclosed debt burdens approximately 14 percentage points higher than Moody’s previous projections, with domestic arrears of close to 12% of GDP largely unreported in official statistics.

Why Stock-Flow Adjustments Matter for Sovereign Ratings

Moody’s research demonstrates a clear correlation between large stock-flow adjustments and weaker governance scores. The agency found that ‘large stock-flow adjustments over time are correlated to weaker scores under our Transparency and Disclosure assessment, as well as in our evaluation of institutions and governance’. This matters because transparency and governance increasingly influence sovereign credit assessments. Rating agencies have significantly enhanced their methodologies to capture these risks, with governance factors now representing approximately 25% of sovereign ratings across major agency frameworks.

The economic logic is straightforward: persistent positive stock-flow adjustments indicate that fiscal deficits may not accurately represent government financing needs. As Moody’s explains, ‘when stock-flow adjustments are positive, a higher primary balance is required to stabilise debt over the long term’. This creates both fiscal and credibility challenges that rating agencies must incorporate into their assessments. For countries with histories of significant adjustments, Moody’s notes it ‘may incorporate debt increasing stock-flow adjustments in our forecasts for sovereigns with a history of significant stock-flow adjustments. Such a track record would also typically lead us to make a more negative assessment of fiscal policy effectiveness’.

Technical Challenges in Debt Restructuring

Transparency issues have complicated recent debt restructuring efforts under the G20 Common Framework. Moody’s highlights that ‘incomplete quantification and classification of claims and the subsequent need for lengthy data reconciliation has contributed to delays in finalising recent debt restructuring cases under the Common Framework process, as in Zambia’. Zambia’s restructuring process took 3.5 years (2021-2024), partly due to transparency complications including debt data verification delays and hidden debt discoveries requiring renegotiation. Ethiopia’s ongoing restructuring (since 2021) demonstrates similar challenges, while Ghana’s relatively faster process benefited from greater initial debt transparency. The framework relies on transparent debt reporting to determine restructuring perimeters and facilitate informed decisions on appropriate relief levels. Recent initiatives include the Joint External Debt Hub (JEDH) for enhanced data collection and various transparency incentives, but progress remains uneven across borrowing countries.

The Path Forward: Transparency as Strategic Financial Tool

The convergence of rating methodology enhancements and transparency requirements creates both challenges and opportunities for sovereign borrowers. Improving fiscal data systems is no longer merely a technical accounting exercise - it has become a strategic imperative for maintaining market access and creditworthiness. Technical recommendations from international financial institutions emphasise comprehensive debt-deficit reconciliation systems, enhanced state-owned enterprise monitoring, and systematic contingent liability tracking. Implementation of Government Finance Statistics Manual 2014 (GFSM 2014) accounting standards provides a framework for more comprehensive reporting.

The rating agency response suggests this trend will intensify rather than moderate. Enhanced governance assessment methodologies, improved off-balance sheet liability analysis, and deeper integration of transparency metrics into credit opinions indicate that data quality will increasingly influence sovereign borrowing costs. For emerging and frontier market sovereigns, this creates clear incentives for transparency improvements. Research shows governance improvements typically result in 1-2 notch rating upgrades over 3-5 years, while poor governance adds 50-200 basis points to sovereign spreads. Conversely, strong transparency frameworks can reduce spreads by 30-100 basis points - representing substantial savings on sovereign borrowing costs.

Conclusion: From Warning to Opportunity

Senegal’s case illustrates how transparency failures can trigger rapid and severe credit deterioration, but it also demonstrates the rating agencies’ increasing sophistication in detecting and penalising such weaknesses. Moody’s comprehensive analysis of stock-flow adjustments provides governments with both a diagnostic tool and an early warning system for potential transparency issues. The message for sovereign debt managers is clear: in an era of enhanced transparency requirements and sophisticated rating methodologies, fiscal data quality has become inseparable from creditworthiness. As Moody’s research demonstrates, addressing these gaps proactively can prevent the kind of sudden, severe rating actions that have characterised recent African debt crises.

Rather than viewing enhanced transparency requirements as burdensome oversight, sovereign borrowers should recognise them as opportunities to strengthen their credit profiles and reduce borrowing costs. The technical capacity building required to implement these improvements represents an investment in long-term fiscal credibility and, ultimately, in more sustainable debt management frameworks.

📺 Watch on Youtube: Rated – with Daniel Cash

Explainer videos on how credit rating agencies shape the world

→ youtube.com/@RatedWithDanielCash

📸 Follow: @RatedWithDanielCash on Instagram

Visual explainers, quotes, and reform insights

→ instagram.com/RatedWithDanielCash

💼 Connect: Dr. Daniel Cash on LinkedIn

→ linkedin.com/in/daniel-cash-61684623

🌐 Visit: www.drdanielcash.com

Writing, research, and reform work all in one place

Barbados Just Tried Something New. Will Credit Ratings Catch Up?

Barbados has launched a regional debt-for-resilience swap designed to unlock fiscal space for climate and social investment. It is being backed by multiple development banks and aims to serve as a regional blueprint. Yet, the real test may lie elsewhere: will the global credit rating system recognise this kind of innovation?

Barbados has launched a regional debt-for-resilience swap designed to unlock fiscal space for climate and social investment. It is being backed by multiple development banks and aims to serve as a regional blueprint. Yet, the real test may lie elsewhere: will the global credit rating system recognise this kind of innovation?

What makes this swap different

The mechanism announced in July represents a significant departure from previous debt-for-nature transactions. This regional facility is backed by four major multilateral development banks: the Inter-American Development Bank, World Bank, CAF, and Caribbean Development Bank. Unlike the bespoke negotiations that characterised earlier swaps - which could take years to structure - this facility promises standardised processes that could reduce transaction times from years to months.

The estimated regional pipeline sits between $2 billion and $3 billion, with Barbados serving as the initial test case. Finance Minister Ryan Straughn confirmed that Barbados will focus initially on a ‘debt-for-social swap to create fiscal space to renew investment in our social sector’. The facility’s ‘resilience’ designation provides broader flexibility than climate-specific swaps, encompassing everything from physical infrastructure to health systems and education.

The connection to the Bridgetown Initiative - Barbados’s broader reform agenda for international financial architecture - positions this as more than a standalone transaction. It represents a practical demonstration of how vulnerable states might systematically access affordable, long-term finance for development priorities.

How rating agencies think about such instruments

Credit rating agencies have developed relatively consistent frameworks for evaluating debt swaps, though their treatment reveals both opportunities and limitations. The primary analytical lens focuses on four key factors: legal enforceability and debt servicing capacity, fiscal space creation and interest savings, presence of guarantees or concessionality, and governance improvements in targeted sectors.

S&P Global’s February 2024 analysis suggested that debt-for-nature swaps are ‘gaining traction among lower-rated sovereigns’ but noted that despite lowering debt burdens, ‘none of these transactions has changed the issuer’s fundamental credit characteristics or led to higher ratings’. S&P’s methodology treats these transactions under its distressed exchange framework, focusing on whether bondholders receive less than originally promised and whether the swap helps the issuer avoid an imminent default.

Moody’s April 2025 upgrade of Barbados to B2 offers a more nuanced picture. The rating agency explicitly cited ‘expectations of higher real GDP growth supported by structural reforms and higher investment in key sectors, including investment in climate resilience efforts’. This represents significant integration of ESG factors into sovereign credit analysis, with Moody’s noting that Barbados is targeting around 5% of GDP in public investment annually in coming years, compared with just 1.3% in 2018.

The upgrade recognised resilience investments as supporting economic growth, even as Hurricane Beryl impacted the economy in 2024. Moody’s observed that real GDP growth remained strong at 4%, partly attributed to ongoing infrastructure and resilience investments. Yet the agency’s treatment of Barbados’s December 2024 debt-for-climate swap - which generated $125 million in fiscal savings - received only indirect recognition in the rating rationale, suggesting that traditional fiscal metrics still dominate over innovative financing mechanisms.

The rating system’s moment of choice

This raises a broader question about whether rating methodologies adequately capture sovereign innovation in climate finance. While rating agencies are independent in their assessments, their frameworks are not immune to evolution - especially as sovereign instruments themselves become more complex. The standardised regional facility could serve as a test case for whether agencies will adapt their frameworks to recognise systematic resilience building rather than treating each swap as an isolated transaction.

Research indicates that environmental risks now affect $4.3 trillion in rated debt globally, yet rating agencies have been slow to systematically incorporate long-term resilience dynamics. Current methodologies emphasise near-term fiscal impacts over longer-term structural changes, potentially undervaluing investments that enhance debt sustainability over time. The UN Economic Commission for Africa has noted this temporal mismatch, highlighting that climate-resilient countries demonstrate lower bond yields and higher sovereign ratings, but with significant lags in rating agency recognition.

The involvement of four major multilateral development banks in the Barbados facility provides credit enhancement that should theoretically improve agency comfort with the mechanism. More importantly, the standardised structure could establish precedents for rating treatment of similar instruments across other climate-vulnerable regions. If successful and replicated, this could force methodological evolution in how agencies assess the creditworthiness of countries pursuing proactive climate adaptation.

Barbados is not asking for special treatment, but for fair recognition of structural improvement. If rating agencies do not adapt their frameworks to properly value resilience investments, they risk creating perverse incentives against exactly the type of sovereign innovation that countries need for long-term stability.

What comes next

The facility will be formally launched at COP30 in Brazil this November, with several Caribbean countries - including Grenada, Belize, and Dominica - expected to join by year-end. Its success will not only depend on interest savings or project delivery - it will depend on whether rating agencies evolve to treat such models consistently as part of sovereign credit assessment.

Will this swap become a blueprint for other regions? Will rating agency frameworks evolve to properly value systematic resilience building? How should we judge rating success in a changing financial climate where traditional metrics may miss the most important dynamics?

Barbados may be small, but in sovereign finance innovation, it continues to set precedent. Whether the global rating system evolves in response - or maintains frameworks that risk undervaluing resilience - will shape how vulnerable countries access capital for years to come. This is not just about Barbados. It is about whether the institutions that shape capital access can evolve fast enough to meet the realities of 21st-century sovereign risk.

If you want more on this story, subscribe to ‘Rated with Daniel Cash’, a YouTube Channel devoted to all things credit rating related!

Between Commitments and Credibility: What I’m Watching for at FfD4

As I write this from Dubai, one week out from travelling to Seville for the Fourth International Conference on Financing for Development, the moment feels significant - not just for the multilateral calendar, but for what it might signal about our collective willingness to confront the architecture of global finance with something more than aspiration.

The financing gap has widened significantly over the last five years, reaching around $4 trillion annually. That stark figure from the first draft outcome document captures both the scale of our challenge and the urgency driving the FfD4 process. As someone who has spent years working within the UN system on financial architecture reform, I find myself cautiously optimistic about what this conference might achieve, while remaining clear-eyed about the distance between commitments and credibility.

The Promise of Reform – and the Risk of Abstraction

Reading through the Outcome Document recently published ahead of the Conference – otherwise referred to as the ‘Compromiso de Sevilla’, there is no question about ambition. ‘We decide to launch an ambitious package of reforms and actions to close this financing gap with urgency, and catalyse sustainable development investments at scale’… ‘We commit to continued reform of the international financial architecture, enhancing its resilience, coherence and effectiveness in responding to present and future challenges and crises’.

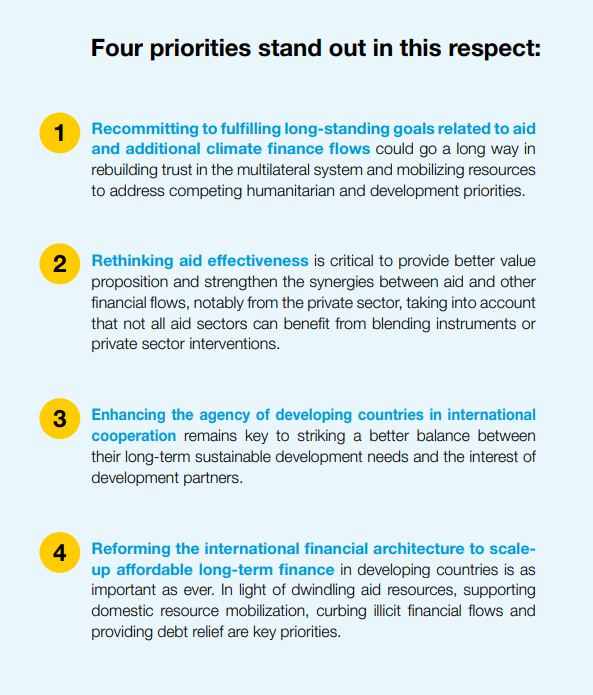

The language is strong. The political commitment to continue to support and engage constructively in the negotiations on a United Nations Framework Convention on International Tax Cooperation represents meaningful progress. The call for development partners to double their support for domestic resource mobilisation and public financial management by 2030 shows real ambition on revenue mobilisation.

Yet throughout the document, there is a familiar pattern: aspirational language backed by mechanisms that often remain vague or untested. It is the perennial challenge of multilateral diplomacy – how to translate political consensus into operational change that countries can actually implement and stakeholders can hold accountable.

Nowhere is this tension more visible – or more urgent – than in how we define and regulate creditworthiness.

Credit Ratings: Leverage Point and Litmus Test

The Structural Problem

Credit rating agencies continue to function as gatekeepers to global capital – but they do so with limited public accountability globally, short time horizons, and a narrow conception of fiscal sustainability. The problem is not simply technical; it is structural.

Consider the methodological constraints: CRAs still heavily discount investments in climate resilience and social infrastructure, treating them as fiscal burdens rather than long-term assets. Their scenario analysis remains stubbornly short-term, typically extending no more than three to five years – far too brief to capture the benefits of education spending, renewable energy transitions, or pandemic preparedness. The reasons for the agencies to operate in this fashion are many and, from their perspective, entirely plausible. Meanwhile, the mechanistic use of credit ratings in regulatory frameworks like Basel III creates self-reinforcing cycles where rating downgrades trigger capital flight, validating the very pessimism that prompted the downgrade.

Perhaps most problematically, there is an asymmetry of power: CRAs shape risk narratives that determine borrowing costs for entire populations, yet they operate with minimal public oversight and limited accountability for the development consequences of their assessments. The oversight that does exist is centred around American and European needs and understandings. Even with this narrow focus, the oversight is targeted, limited, and certainly not transparent (see the argument over deanonymising SEC investigations, as one example – I was a signatory to this call headed by Americans for Financial Reform and fully believe that deanonymising regulatory intervention may well make sense for the regulator, but not for the public).

Activating the Solutions We Already Have

This brings us to paragraphs 44+ of the Outcome Document, which mark a genuine watershed in recognising these dynamics. Three commitments in the draft deserve real attention:

First, the call on CRAs to refine their methodologies to account for investments, lengthen time horizons for credit analysis, and publish long-term ratings based on scenario analysis. This directly addresses the short-termism that penalises countries investing in climate resilience or social infrastructure.

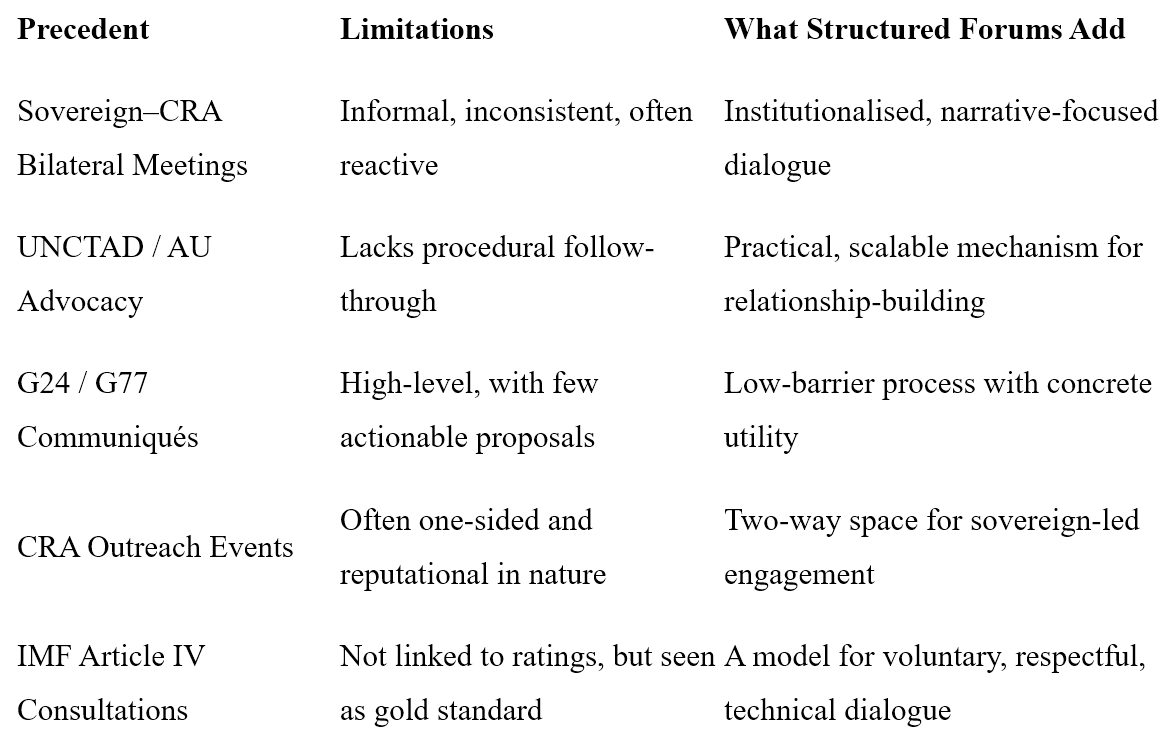

Second, ‘We decide to establish a recurring special high-level meeting on credit ratings under the auspices of ECOSOC for dialogue among Member States, credit rating agencies, regulators, standard setters, long-term investors, and public institutions that publish independent debt sustainability analysis. The meeting will include updates on the Secretary General’s efforts to engage with credit rating agencies, discussion on the use of credit assessments, exchanges on good practices for regulation of credit rating agencies, and sharing of perspectives on credit assessment methodologies’. Creating structured space for this conversation within the UN system represents a significant institutional innovation and a unique commitment in this new space for the UN.

Third, the recognition that potential miscalibration of risk-weightings in financial regulation, such as Basel III may be hampering development finance. This technical-sounding language masks a crucial point: when regulatory frameworks mechanistically rely on credit ratings, they can amplify rating biases and create self-fulfilling prophecies of financial exclusion.

It is worth making something clear. The point of this process is not to be prescriptive with what needs to happen. Take the ECOSOC annual meeting that has been earmarked. The details over what should be developed within the meetings are not contained in the Outcome Document, and for good reason. What needs to be developed, what is reasonable or workable, and what the objectives should be, need to be co-created, not prescribed from upon high. This, I believe, is the only way progress will be witnessed and, of course, is the right approach.

The ECOSOC Annual Meetings

I think it is worth focusing on the establishment of annual meetings with the primary players within the world of credit ratings for a moment. I play a very small part in a much larger agenda which has brought us to this point, and it ought to be recognised. I can recall more meetings than I would care to reveal where the idea of credit ratings being central to the prevailing problems facing the required development of large proportions of the globe was instantly dismissed. ‘That’s too technical’, or ‘that makes sense, but what are we supposed to do about it?’ On reflection, the dismissal, or at best muted agreement was absolutely valid. On the face of things, the credit rating space is too technical. On the face of things, there is very little space for impact or influence. But, with perseverance and communicating these issues in different ways for different audiences, the agenda has been fully developed. Now, the credit rating question is front and centre. I can attest to this personally. In conferences and multilateral meetings the world over, the credit rating-related events are standing-room only. This is represented in the Outcome Document and it is worth celebrating.

It is worth celebrating because now the real work can get started. Never before in the development space have the credit rating industry been represented as it is now. There are many reasons why the credit rating agencies are now responding and engaging. From a self-interest point of view, they are being put on the international agenda and cannot afford to be absent. They must inject their own understanding, their own side of the story. But, what I have seen, admittedly to differing levels, is a genuine willingness to engage in ways which are not ‘normal’ for the CRAs. There is still a natural organisational defensiveness but this is to be expected. But, now, there is a growing sense that engagement and co-creation can be a benefit for the agencies, not just a way to quiet the international focus. Innovations that are in the pipeline are garnering genuine engagement from the rating agencies and, for this, they should be encouraged. What strikes me through this whole process is that for the world we want to see, the rating agencies will need to be onside. The modern development of credit and debt demands it.

What I Hope to Hear in Seville

So what would progress look like in Seville? For me, it is about listening for signs of activation - moments where ambition moves into architecture.

Are the major CRAs prepared to treat this not as a reputational defence, but as a collaborative opportunity?

The document’s call for transparent, accurate, objective and long-term model-based credit assessments challenges fundamental aspects of current rating methodologies. The most promising signals would be CRA willingness to engage in structured peer review and methodological transparency. Followers of my work will know that I am an active campaigner for taking a realistic approach when it comes to the credit rating agencies. I would suggest that those who think the CRAs will rip up their methodologies to take a development approach to rating creditworthiness will be sorely disappointed. This is for good reason… this is not the job of the CRAs and nor should it be. However, incremental methodological evolution should be demanded and the CRAs ought to meet that demand. There are other areas of evolution which would have more impact – like the credit rating committee stage – and more focus is needed on those aspects.

Will Member States take seriously the opportunity to build public rating infrastructure as a complement, not a confrontation?

The document’s language on public alternatives represents a diplomatic breakthrough, but implementation will require institutional capacity and political courage. It may also require a wide re-evaluation of what is possible, what the objectives ought to be from such public investment, and ultimately what may be the best way to implement such an approach. Public initiatives, like the forthcoming AfCRA initiative, face a similar problem which has prevented public alternatives to the private offering of the CRAs: how do you differentiate while remaining credible? If an offering is the same as the Big Three, then why would anybody use it? If the offering is different, then how do you answer questions of bias etc? I argue that for the likes of AfCRA, technical innovation is the route to success rather than focusing on the outcome, but time will tell on how AfCRA is received by the market and its players.

Final Reflections - Where This Might Go

We cannot afford a retreat from multilateral cooperation. These global challenges far exceed the capacity of any single state to respond. That conviction, stated early in the Compromiso de Sevilla, captures both the stakes and the opportunity at FfD4.

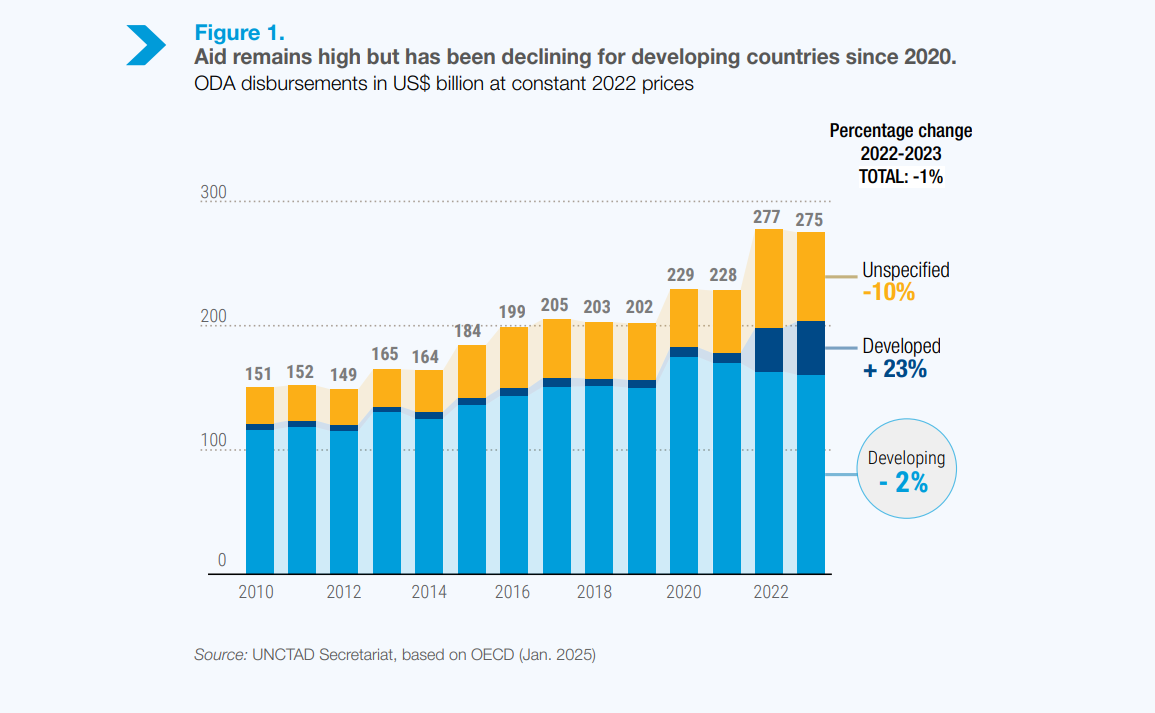

The multilateral moment is undeniably fragile. Even as the draft was being finalised, the world’s largest (USA), fifth-largest (UK) and eighth-largest (Netherlands) ODA providers announced significant aid cuts – a sobering counterpoint to the ambition on display. Political winds are shifting in ways that make international cooperation more challenging, not less.

Yet I remain convinced that the window for meaningful credit rating reform – and broader financial architecture reform – is open, even if only partially. The technical understanding of how these systems work has never been stronger. The political coalition for change continues to grow, driven by countries that have experienced firsthand how rating methodologies can constrain their development space.

What gives me hope is not just the language in the FfD4 Outcome Document, but the quality of engagement I’ve seen in preparatory discussions. Finance ministers who once viewed credit ratings as immutable facts of economic life are beginning to understand them as methodological choices that can be influenced and improved. Multilateral institutions that once treated CRA assessments as gospel are starting to develop more nuanced approaches to risk assessment.

Reforms that once felt radical are now on the table. The architecture of global finance will not, and cannot shift all at once – but it is beginning to creak in new directions. If we hold steady, and act with clarity, we can help it move.

I’ll be in Seville next week not just as a speaker and an observer, but as someone who believes these conversations matter for how global finance serves development. If you are following the process, I encourage you to stay engaged, ask hard questions, and keep pushing for systems that are not just technically sophisticated but fundamentally fair. If you are in Seville next week, please reach out!

It is time we remembered that creditworthiness is not just a number – it is a narrative we shape together.

Putting Credit Ratings On-Chain: A New Infrastructure for Trust?

In June 2025, Moody’s took another quiet but significant step into the blockchain space: they issued a live credit rating on a tokenised municipal bond, placing that rating directly onto the Solana blockchain. Working with Alphaledger, this was not just a pilot - it was a functioning credit assessment delivered through blockchain infrastructure, readable and actionable by smart contracts in real time.

Moody’s had analysed this field in 2023, but this move presents the agency’s opening gambit. It signals Moody’s intent to explore blockchain not just as a data feed but as a delivery system for creditworthiness itself. This is not just about technical integration, it is about whether creditworthiness can be translated into programmable trust.

What Are On-Chain Credit Ratings?

Traditional credit ratings exist as reports and data feeds that humans interpret. On-chain credit ratings exist as blockchain data that smart contracts consume directly. When Moody’s rated the municipal bond on Solana, they embedded their assessment into the same infrastructure where automated financial decisions happen.

A tokenised bond can now have its credit rating updated in real-time on the blockchain where it trades, theoretically. Smart contracts governing lending protocols can potentially and automatically adjust terms based on rating changes. The rating would become part of the asset’s digital DNA rather than external commentary.

This infrastructure may become essential as real-world assets migrate onto blockchains. Tokenised municipal bonds, corporate debt, and complex financial products will all need creditworthiness assessments that blockchain protocols can understand and act upon.

Why This Matters

The scale makes this urgent. Boston Consulting Group projected tokenised real-world assets would reach $16-19 trillion by 2030, although other predictions are more conservative. Nevertheless, there could be trillions in assets needing credit assessment infrastructure that traditional rating agencies have never had to provide. The question is whether that infrastructure will extend existing systems or create entirely new ones.

“A tokenised bond can now have its credit rating updated in real-time on the blockchain where it trades, theoretically.”

Consider MakerDAO’s evolution. Their DAI stablecoin now includes real-world assets like U.S. Treasuries and real estate loans as collateral. The protocol tracks these assets on-chain, but assessing their credit quality requires off-chain analysis translated into on-chain parameters. The rating could become a bridge between different information environments.

Brand Power vs Technical Functionality

Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch built their authority through consistent methodology, regulatory relationships, and institutional trust. That brand equity represents real economic value - pension funds can invest in their rated instruments because regulators recognise those ratings, for example.

But on-chain environments might not care about brand equity the same way. When smart contracts need to liquidate collateral or adjust lending terms, they need machine-readable data that is frequently updated and integrated with blockchain infrastructure. The question is whether traditional agencies can provide that functionality fast enough.

Credora focuses on real-time credit analytics for crypto lending using on-chain data. Xangle provides crypto asset ratings designed for digital-native investors. These are not replicating Moody’s methodology – they are building credit assessment tools specifically for blockchain environments.

The Solana Foundation positions their blockchain as ideal for ‘institutional-grade applications’ because of technical capabilities like high throughput and low costs. The implication: institutional adoption depends on infrastructure that can handle scale, not just familiar brands.

Neither Fitch nor S&P has announced similar on-chain rating pilots, though both research tokenisation actively. Their absence from early experimentation might indicate caution - or different approaches to the same challenge.

Signal and Noise

Credit ratings traditionally reduce noise by converting complex financial information into simple signals. Yet, blockchain environments generate different noise that traditional methodologies were not designed to handle.

On-chain data provides unprecedented transparency into asset movements and transaction patterns, but also creates information overload. A tokenised real estate fund might have perfect transaction records, but what do those tell you about underlying property values or local market conditions? The blockchain provides the signal; interpretation still requires human judgment.

“On-chain ratings might trigger financial decisions at speeds that make traditional oversight impossible”

Centrifuge exemplifies this challenge with supply chain financing and invoice tokenization. They are making credit assessment more transparent and automated, but ensuring automation does not sacrifice accuracy for speed remains difficult.

This creates tension between ratings that are human-interpretable versus machine-actionable. Traditional agencies excel at the former; blockchain-native systems target the latter. Companies that master both might define credit assessment in tokenised markets.

Open Questions

Will established agencies maintain dominance by adapting to blockchain infrastructure, or will technical advantages favour new on-chain players? The Moody’s pilot suggests traditional agencies take this seriously, but one experiment does not determine market structure.

How do regulators evaluate machine-readable risk data that updates in real-time and triggers automated decisions? Traditional oversight assumes human decision-makers interpreting reports. On-chain ratings might trigger financial decisions at speeds that make traditional oversight impossible.

What happens when an on-chain rating is disputed? Traditional ratings can be revised through established appeals processes. Blockchain records are immutable by design. The infrastructure for handling rating disputes in decentralised systems does not exist yet.

How do you verify off-chain assets backing on-chain tokens when the rating system itself lives on-chain? This creates verification loops that traditional agencies solved through direct issuer relationships and private financial access. Blockchain systems might need entirely different due diligence approaches.

These are not just technical questions – they are about market structure, regulatory frameworks, and institutional trust. We are early in this conversation, and those who help shape it will likely determine how credit assessment works for the next generation of financial infrastructure.

The Moody’s municipal bond pilot was small, but significant: a traditional institution testing whether their core function works in a fundamentally different technological environment. Whether they succeed, and who joins this experimentation, will shape how we think about credit, trust, and financial infrastructure in an increasingly tokenised world.

For those working on tokenisation infrastructure or credit assessment frameworks, I’m tracking these developments closely through my work at CRRI. The intersection of traditional finance and blockchain governance raises questions that deserve serious analysis - not just from technologists, but from those who understand how trust and risk assessment actually function in complex financial systems.

Connect with me on LinkedIn if you’re exploring similar questions, or follow my analysis here on my website.

Private Credit: Seeing the System Clearly

The headline caught my attention: ‘Private credit could “amplify” next financial crisis, study finds’. It appeared in the Financial Times recently, summarising findings from a comprehensive report from Moody’s Analytics that uses sophisticated econometric tools to examine how private credit has become more central to financial contagion during stress periods.

This is not my usual domain - I am more at home analysing the governance structures that shape financial decision-making than dissecting loan covenants or fund structures. But as someone who has spent years watching how systemic risk migrates through financial systems, I find myself drawn to what these developments might mean for how we understand and manage financial stability.

The Moody’s study, published in this month, employs principal component analysis and Granger-causality network modelling to map interconnections across the financial system. Their findings suggest something significant: during periods of stress, business development companies (BDCs) - their proxy for private credit - have become more prominent in the network of financial linkages, while banks have become relatively less central. Moody’s argues the financial system has shifted from a ‘hub and spoke’ structure centred on banks to a denser, web-like configuration - where private credit now occupies critical nodes.

The Growth and Scale

Private credit - essentially nonbank lending to companies, often middle-market firms that fall between traditional bank loans and public bond markets - has grown explosively since the global financial crisis. From a niche asset class, it has expanded to roughly $2 trillion in global assets under management, with about three-quarters concentrated in the United States. To put this in perspective, it now rivals the high-yield corporate bond and syndicated leveraged loan markets in size.

“Unlike public markets, most private credit offers no real-time pricing and relies on bespoke contracts”

This growth was not accidental. Post-crisis banking regulations tightened capital and liquidity requirements for traditional lenders, creating space for institutional capital to fill the gap. Private credit funds stepped into this void, offering speed and customised terms to borrowers in exchange for higher interest rates than typical bank loans. What began as direct lending to middle-market companies has since expanded into specialty finance, asset-based lending, and increasingly complex structures.

Emerging Systemic Concerns

The concerns are not just about size - they are about structure and visibility. Recent analysis from multiple regulators highlights several interconnected risks. The IMF’s April 2024 Global Financial Stability Report warns that private credit’s growth creates potential risks if the asset class remains opaque, noting that ‘credit migrating from regulated banks and relatively transparent public markets to the more opaque world of private credit creates potential risks’.

The Moody’s study documents how this opacity combines with increasing interconnectedness. Banks are becoming more involved in private credit through partnerships, fund financing, and structured risk transfers that allow them to maintain economic exposure while shifting assets off balance sheet. While such arrangements may offer capital efficiency, they can also obscure the true distribution of risk.

“What began as direct lending to middle-market companies has since expanded into specialty finance, asset-based lending, and increasingly complex structures.”

Three particular vulnerabilities stand out from the research. First, layered leverage creates cascading risks - borrowers with high debt-to-EBITDA ratios funded by funds that themselves use subscription lines and other credit facilities. The Moody’s report notes that private credit managers are increasingly financing their loan portfolios through private collateralised loan obligation structures, with well over $100 billion of private credit CLOs outstanding. This introduces another layer of leverage and structural complexity that is not always visible to end investors.

Second, liquidity mismatches are emerging as funds experiment with semi-liquid structures to attract broader investor bases. These models introduce a potential duration mismatch, as funds commit to holding long-dated, illiquid assets while offering investors periodic liquidity supported by credit lines or cash buffers.

Third, transparency gaps complicate risk assessment. Unlike public markets, most private credit offers no real-time pricing and relies on bespoke contracts. As the Moody’s report observes, private credit’s lack of standardisation and limited disclosure complicate efforts to monitor its risks. Mark-to-model assets are vulnerable to swings in market confidence, and when pricing gaps emerge, attention quickly shifts to the balance sheets of those holding similar exposures.

Recent regulatory analysis supports these concerns. The Federal Reserve’s May 2025 research reveals that banks have become a key source of liquidity for private credit lenders through credit lines, with 22% of large U.S. banks’ commercial loans now going to private credit-backed firms. The European Central Bank warns of ‘hidden leverage and blind spots’ from growing interconnections between banks and private market funds, noting that exposures ‘can involve layered leverage’.

Shadow Banking Echoes?

These developments inevitably invite comparisons to pre-crisis shadow banking, though the parallels are not straightforward. Recent academic analysis reveals structural similarities: 63% of private credit loans lack standardised covenants compared to 41% in 2007 syndicated loans, and 35% of funds use leverage exceeding 2:1, approaching 2006 CLO levels.

Yet, there are meaningful differences. The investor base is fundamentally different - dominated by pensions, insurers, and endowments rather than the retail-driven flows that characterised pre-crisis structured products. The Systemic Risk Council’s May 2025 report explicitly places private credit within ‘shadow banking’s global risks,’ while acknowledging that longer lock-up periods may reduce near-term liquidity risks compared to pre-crisis structures.

The Moody’s study captures this evolution well: ‘Rather than a hub-and-spoke centred on large banks and broker-dealers as was the case in the GFC, the network is more distributed. BDCs and other nonbanks have become more central to network connectivity over time, while banks’ centrality has somewhat diminished.’

Risk has not vanished - it has changed form, location, and visibility. Where pre-crisis risks concentrated in bank-backed off-balance-sheet vehicles, today’s risks may be dispersed across private vehicles with limited regulatory visibility.

Financial Governance Implications

From a governance perspective, what strikes me most is how this evolution challenges our existing frameworks for understanding and managing systemic risk. We have spent the post-crisis years strengthening bank oversight and improving transparency in public markets, but systemically important activities have quietly shifted to spaces with different oversight regimes.

The Moody’s report argues that regulators should consider expanding the regulatory perimeter to include significant private credit funds, enhance transparency through improved reporting requirements, and integrate private credit trends into macroprudential policy frameworks. They suggest that central banks should consider how they would respond if a systemic event in private credit markets materialised, noting that traditional lender-of-last-resort tools may not reach these markets directly.

This is not about stifling innovation or imposing bank-like regulation on fundamentally different institutions. It is about ensuring that our risk monitoring tools can see clearly across the financial system as it actually operates today, not as it operated fifteen years ago. The Financial Stability Board’s 2024 annual report acknowledges this challenge, noting ‘private credit is growing rapidly and there is increasing evidence of its connections with the banking system and with institutional investors’ while highlighting the opacity that makes assessment difficult.

The International Organization of Securities Commissions has begun updating frameworks around liquidity risk management and valuation principles for collective investment schemes, indirectly addressing some transparency issues relevant to private credit. However, these efforts remain fragmented across different regulatory domains.

The Path Forward

I enter this conversation not as a private credit expert, but as someone who has watched how financial systems evolve and how governance structures struggle to keep pace. What concerns me is not necessarily the growth of private credit itself - it appears to serve legitimate economic functions and has attracted sophisticated institutional investors who understand the risks they are taking.

What concerns me is the possibility that we are creating new systemic vulnerabilities without adequately updating our tools for seeing and managing them. As the Moody’s study notes, ‘the lack of transparency allows risks to accumulate. Data gaps remain a serious issue in the current landscape, as there is limited information on loan covenants, true portfolio valuations, and the overlap of fund investors’.

This echoes past moments - like the 1990s derivatives boom or the 2000s structured credit surge - where innovation moved faster than oversight. The lesson from those episodes is not that innovation is inherently dangerous, but that transparency and appropriate oversight need to evolve alongside market structures.

If private credit is here to stay - and it is - we owe it to ourselves to see it clearly. The consequences of not doing so are all around us, if we care to look.

Simplifying Sustainability - Or Surrendering It? How Europe’s ESG Rollback Undermines Ratings and Credibility

Green Central Banking’s recent analysis of the EU’s Omnibus Proposal deserves careful attention – not because it breaks news, but because it captures a deeper unease about the direction of EU sustainability governance. In their piece ‘EU regulators warn omnibus proposal could increase financial risk,’ they have captured something that extends far beyond technical regulatory adjustment. The EU’s sustainable omnibus package promises to simplify climate reporting requirements for companies, reducing the scope for 80% of firms, but what Green Central Banking reveals is a deeper tension between administrative convenience and systemic integrity.

This post offers a response to their arguments; not to disagree, but to extend and deepen them. Green Central Banking raises a crucial point: this isn’t just a recalibration of reporting scope. It may be the first visible crack in one of the EU’s few remaining pillars of policy coherence.

What the Omnibus Changes – and Why It Matters

The Omnibus Proposal aims to reduce disclosure requirements under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), potentially exempting 75-80% of companies from mandatory sustainability reporting. The changes would raise thresholds so that only companies with more than 1,000 employees or revenue exceeding €50 million would face mandatory reporting requirements, with smaller firms able to report voluntarily.

The stated rationale is compelling and deserves recognition: reducing administrative burden on small and medium enterprises, improving proportionality in regulatory requirements, and addressing legitimate concerns about compliance costs. Business groups have welcomed these changes as necessary realism in the face of regulatory overreach. The European Commission has emphasized that the Omnibus represents simplification, not abandonment of the Green Deal agenda.

Humberto Delgado Rosa, director for biodiversity and environment at the European Commission, said during a panel at the Sustainable Investment Forum Europe conference in Paris that the simplification process doesn’t mean deregulation for the sake of less red tape: ‘The simplification agenda is a very legitimate one, one that aims to maintain competitiveness, because without it we would not be able to move towards sustainability.’

These are reasonable arguments, reflecting genuine tensions between regulatory ambition and economic practicality. But proportionality without visibility is a dangerous trade. The very firms seen as too small to report may still carry climate, supply chain, and governance risks that accumulate systemically.

What the Risks Really Mean

Green Central Banking has identified where this reasonable-sounding adjustment creates unreasonable systemic problems. As they report, the European Central Bank has cautioned the EU from drastically reducing the scope of the corporate sustainability reporting (CSRD) and due diligence directives (CSDDD), warning that the changes could increase risk for the economy, investors and the EU’s wider sustainable goals.